The European Union's new Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) sets ambitious targets for plastic packaging, including full recyclability by 2030 and increased recycled content by 2040, driving stricter compliance. The upcoming INC-5 treaty will address plastic production limits and waste management, aiming for a global pact to combat plastic pollution. Together, these initiatives put pressure on industries to transition to a circular economy while reducing reliance on single-use plastics.

Yet definitions matter as one can only monitor, mitigate, and monitor that which one can define.

Why it matters

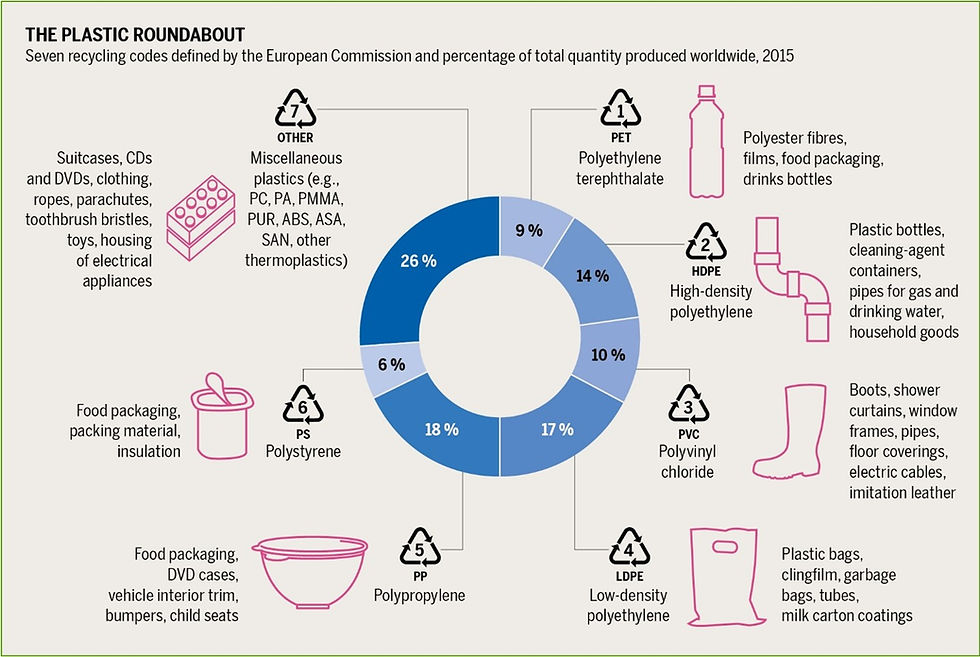

Understanding the resin identification codes informs reducing waste.

EU’s Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation is driven global change.

Extended Producer Responsibility Schemes (EPRs) are defining liabilities for plastic packaging produced.

But many other chemicals are components of plastics, and these too must be addressed.

Legal Drivers

The European Union's new Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation targets are:

90% of beverage packaging (including plastic bottles and aluminum cans) collected separately by 2029.

Mandatory deposit return schemes to cover all 27 EU countries from the 15 countries currently with policies in place.

A standardized calculation of recycling rates across the EU.

All plastic packaging to be recyclable by 2030, recycling not yet defined.

10% of packaging for both alcohol and non-alcohol beverages with exclusions to be reused as packaging by 2030.

30% of recycled content in non-food and some food-grade plastic packaging by 2030, depending on type of plastic.

Ban some types of plastic packaging and single-use plastic products.

Meanwhile, Extended Producer Responsibility Schemes (EPRs) requiring companies to pay for end-of-life management of the products they produce are increasing with some countries developing policies already such as Austria and Germany. This set of policies are improving addressing risks of under-reporting, insufficient costs to drive change, and the need for a legal definition for “designed for material recycling”.

Watch this space as global plastics treaty negotiations (INC-5) in November may increase regulatory innovation globally.

Resin Identification Codes and the Plastic Roundabout

Since 1950, over 8.3 billion tons of plastic have been produced, equivalent to the weight of 2 billion African elephants.

Alarmingly, 55% of plastics are discarded within 6 seconds of use, and single-use plastics may become our era's lasting symbol.

Plastics currently account for 6% to 9% of oil and gas greenhouse gas emissions, and if trends continue, they could reach 13% of the global carbon budget by 2050 under the Paris Agreement 2 degree Celsius commitments.

Packaging makes up 36% of plastic production, with 85% ending in landfills or as unregulated waste, costing the global economy $80 to $120 billion annually.

While the most common plastics in packaging are listed below. Each of these common plastics have distinct chemical production processes and properties, with different corporations in their supply chains, plastics contain thousands of other chemicals, too.

First some definitions:

Plastic: The most effective definition of plastic describes it as a material primarily composed of a polymer, potentially with added substances, which serves as a key structural component of products. Natural polymers that have not been chemically modified are excluded.

Polymer: A polymer is a substance made of molecules formed by repeating monomer units, with variations in molecular weight depending on the number of these units.

Single-use plastic: Single-use plastic is a product that is made wholly or partly from plastic and that is not conceived, designed or placed on the market to accomplish, within its life span, multiple trips or rotations by being returned to a producer for refill or re-used for the same purpose for which it was conceived.

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) ((C10H8O4)n and EC #101-121-858) is a plastic used for bottles, trays, clothing fiber, carpets, and strapping.

High Density Polyethylene (HDPE) ((CH2-CH2)n EC #919-651-5) is a plastic used for bottles, snack food trays, toys, pipes, and furniture.

Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) ((CH2-CHCl)n and EC #924-145-2) is used for pipes, cable, synthetic leather, door frames, and credit cards.

Low Density Polyethylene (LDPE) ((CH2-CH2)n EC #929-000-7) is a plastic used for films, bubble wrap, flexible bottles, and bottle tops.

Linear Low-Density Polyethylene (LLDPE) ((CH2-CH2)n EC #929-000-7) is a plastic used for films, bubble wrap, flexible bottles, and bottle tops.

Polypropylene (PP) ([CH2-CH(CH3)]n and EC #100-117-813) is a plastic used for food bottles, crates, straws, and carpet fibers.

Polystyrene (PS) ([CH2-CH(C6H5)]n and EC #100-105-519) is used for single use cutlery, coat hangers, and toys.

Expandable polystyrene (EPS) (C9H8, EC #935-499-2 and PubChem #24755) is a plastic used for single use cutlery, coat hangers and toys.

Round and Round the Plastic Roundabout About We Go

The plastic roundabout illustrates how plastics are labeled during production.

Resin identification codes (RICs), introduced in 1988 by the Society of the Plastics Industry, categorize plastic types, but they are often misunderstood. These codes do not guarantee recyclability; they merely indicate the one of the resin types used in the packaging with the label.

Furthermore, RICs are not globally standardized, contributing to confusion, as recycling processes differ by region. With the increasing complexity of plastic products, there is growing pressure to expand the RIC system to better address these variations.

A common misconception for consumers is that these symbols are an indicator for recyclability. In fact, it just identifies the type of material.

The other misconception is that it is an international standardized identification, however, it is local – the definition can change by country. There is no known ISO equivalent to the RICs standard as shown in the plastics roundabout.

Finally, there is pressure from industry to increase the number of RICs categories due to the complex nature of many different plastic products.

Missing Additives and the Plastic Roundabout

Every plastic item contains additives that determine the properties of the material and influence the cost of production.

Typical additives include stabilizers, fillers, plasticizers, colorants, as well as functional additives such as flame retardants and curing agents, and intentionally added substances.

Nevertheless, the identities and concentrations of additives are not listed on products.

There are about 7,000 plastic additives used globally.

A randomly chosen plastic product generally contains around 20 additives.

Additives are not listed on products.

Over 400 plastic additives are used in the EU in high volumes.

A study found 10,547 intentionally added substances present in plastics (Wiesinger, 2021).

Many additives are hazardous. A 2018 study found that 3,377 and 906 chemicals are potentially associated with plastic packaging. Out of these, 148 have been identified as most hazardous (Groh et al. 2018).

When plastic products are recycled, it is highly likely that the additives will be integrated into the new products. Absence of transparency and reporting across the value chain often results in lack of knowledge concerning the chemical profile of the final products. For example, products containing brominated flame retardants have been incorporated into new plastic products.

Conclusion

The European Union's new Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) implementation process needs to also address the thousands of chemicals that are added to plastics, used, and then disposed of, many of which may whose harm is unknown.

Comentarios